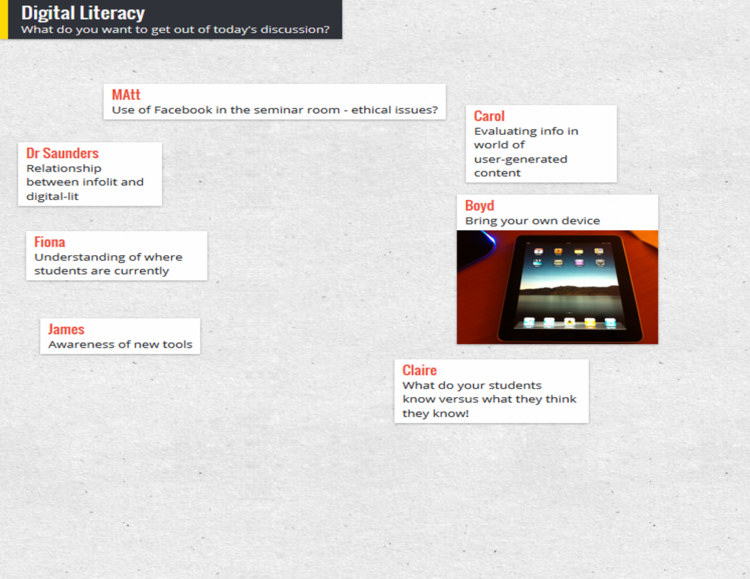

Emma Shaw is the Library Manager and Liaison Librarian (Medicine) at Imperial College London. I while ago I saw her tweeting about the use of Padlet in her teaching sessions - students were using it in groups to come up with search strategies for healthcare-related databases. I like Padlet anyway, but I loved this use of it - so immediately beneficial, practical, and indeed stealable! So I asked Emma to write a guest post about the whole process, and she kindly agreed. Here's an example of the use of padlet she examines below.

I’m a Liaison Librarian at Imperial College London supporting medicine, along with another 4 Liaisons. Amongst a heavy timetable of information skills training for undergraduates and postgraduates, we have for several years been running a couple of Library skills workshops which are embedded in the MBBS Medicine course timetable for the 1st year medical students. We were using the traditional presentation slides telling them about the Library and how to access it, along with a hands on database searching component using the PubMed database. The database searching was taught in the form of a paper based tutorial handout. The students would sit in the computer lab and work through it for 20 minutes whilst also having the opportunity to ask questions. More recently I would go away and wonder whether they would really apply what we were teaching, in the format we were using. I asked myself if it was really meaningful for them, particularly as it was all new to them and we were teaching them how to look up research on a database, when they hadn’t even started using journal articles yet.

The other reason it got me thinking was, Information literacy is not an obvious skill that screams out ‘you need me in your life’ so you therefore need to convey it to the students in a way that makes them realise that they do. Especially when they have other priorities and a timetable jam packed with medical training. I’ve learned and observed over the years of teaching information skills that, in order for them to understand its direct use, to see its value and engage, they need to see it in context. When I say in context, I mean actually directly relating what they are learning in front of them, to a specific area in their coursework or even clinical practice. Rather than just telling them this is stuff they need to know now and in the future. This led me to question if, our presentation slides and paper tutorial were engaging and putting it in context enough. Could there be a better way of delivering the content so they engage with us, and see its direct value?

Feedback from the students about how we could develop the session included comments like:

“Maybe have an example of an assignment similar to what we would have this year and show how we might use online resources for researching that assignment.”

“Interactively doing it together with the students instead of following instructions on a page.”

This made it apparent that we were right to question this, and that it was a good time to reconsider the delivery of our training. We could see why PowerPoint slides were just not cutting it anymore, they needed interaction and context to stay engaged. On top of this, in the MBBS Medicine course, they were already being presented with e-learning modules, and using different teaching methods and technology. I could then see that very shortly our presentation slides and paper based database tutorial was not going to be enough anymore, and that our sessions were in danger of becoming irrelevant. We needed a fresh and new approach.

I had various sources of inspiration for revamping the workshops. We just so happened to have a visit from Caroline Pang, Director of the Medical Library at Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Singapore. One of Imperial College London’s partners. She demonstrated what library training they offered for Medical students. This consisted of initial training on the Library and database searching. They were then given a clinical question from the course tutors, and had to work together in groups to form the best search strategy to answer it. She had a whole day dedicated to this project as well as the presence of the tutors. This looked like a really good approach, not only was it more engaging by getting the students to actively search for a given question, but it was also relevant to the course content so they could directly see its value. If we wanted to do something similar however, the problem we faced was we only had 1.5 hours for each session!

It was then one day at a meeting with tutors from the MBBS Medicine course that, the idea of Flipped learning was presented to me. I won’t go in to too much detail about it as you can find a very good definition here by Professor Dilip Barad (Ph.D.). It’s essentially where work is given to the students to be done before the session e.g. a video lecture, or tutorial to work through. The session is then dedicated to applying the knowledge they have learnt from the pre-sessional work, through activities and group work and allowing them to ask questions. In this way it becomes student centred learning as opposed to trainer centred.

To be honest the flipped learning approach initially filled me with dread! There was the worry of giving them pre-sessional work to do with the risk of them not doing it. It also seemed like a lot of work and preparation, as well as the fear of having to get the students in to groups and managing them. Also having many other duties aside from training, it’s very easy to just slip in to the habit of repeating the same old slides each year. It’s easy, it’s safe. However, if it would improve engagement it was worth a try, and I thought this would be an excellent model for our teaching. It would allow us to save some time in the session by getting the students to do the straight forward PubMed tutorial before the session. This would then allow us to try out the database searching exercise in groups, which we didn’t think we would have time for. We could dedicate time in the session to getting them to do real searches on PubMed, using related topics in up and coming assessments, with the trainers feeding back to the groups as they did the searches. This would allow for more engagement and they would directly see the use of searching a database, by pulling up relevant articles that could be of use for their assessments.

The final plan for the session consisted of an online PubMed database tutorial created using Articulate software. This was essentially a series of online slides taking the students step by step through using PubMed, which we hosted on the Blackboard platform. We emailed the students a week in advance via the Medical School to ask them to do the online tutorial before the session. To encourage them to do it, we mentioned that it would be for a group exercise in the session. We then sent a reminder a couple of days before the session for good measure. Some good advice I got from an e-learning technologist was to give them an approximate time of how long the tutorial would take, so they could plan it around their schedules. We aimed for 30 minutes which we thought they would see as achievable.

For the session, we refined our slides on the Library induction section. We then did a brief summary of what they should have learnt from the PubMed tutorial and gave an opportunity for questions. There was some debate on what to do if the students didn’t do the tutorial before the session. Should we include a more detailed summary in case, or would we run the risk of disengaging the students because of the duplication of information? We decided to go with a very brief summary just confirming points from the tutorial. We would then play it by ear and adapt the session if necessary. We then presented them with a search question related to a future assessment and arranged the students in to small groups and asked them to come up with a search strategy for that question. To provide the students with more feedback in the session and to give it a competitive edge (another bit of advice from a tutor that they liked competition!), we added some blended learning in to the mix. We used an online tool known as Padlet for the groups to add their search strategy to, for which we could then feedback to all the students how they all got on with the task. An example from one session is below.

The first sessions we ran in 2016 went very well and we had over 80% of the 320 students do the pre-session tutorial. As it was successful we ran it again last year in 2017 and over 90% of the students did the pre-session tutorial. The group exercises went well, and we could really see the students engaging with the task and coming up with good search strategies.

The feedback was mainly positive and gave the impression that our new teaching method was working. The following comments were from 2016:

“Clear explanations; the delivery was concise. The activities helped us put the skills into practice.”

“It's really nice to practice searching in class and in group and it really helps when comparing different searching methods within groups.”

Some Feedback from 2017:

“Expanded on the pre reading material and explained things more clearly and gave sufficient exercises to ensure I actually understood the methods of searching databases”

“Learnt new and useful techniques for searching up articles. The session was interactive and fun. Everything was explained well and thoroughly.”

In terms of negative comments, in 2016 we had a few to do with some of the session’s content repeating parts of the pre-session tutorial. As these were our first sessions, we hadn’t yet got the balance right in terms of summarising the tutorial, so we then adapted this for the sessions in 2017 to avoid this. For the 2017 sessions, a few comments said it was a bit rushed, and they wanted more searching examples. They also struggled with some of the concepts like Subject Heading searching, and found it too advanced. This could potentially be because some of the students did not do the tutorial beforehand, but I think we perhaps also need to consider more about those students who learn at different speeds. This is a challenge when teaching 45+ students per session and with the time constraint. However, this is something to bear in mind for the next sessions, and to perhaps offer opportunities for optional follow up training on a 1-2-1 basis for those who require it.

Overall it’s been a real success. Not only do I put this down to the hard work by the Liaison team but, also down to the fact we had really good support from the tutors from the Medical School who always ensure to make it clear to students that information literacy is a crucial part of the curriculum. For anyone wanting to try Flipped learning, I would therefore always recommend getting the faculty on board. Despite all the preparation work, we also enjoyed delivering the session. It was a really good experience actually going around the room and engaging with the students and giving feedback, instead of mainly stood in front of PowerPoint slides and answering questions.

For anyone interested in looking at the session content, such as the online PubMed tutorial please feel free to get in touch.