Part 3 of the Instagram mini series (here’s the introductory part one, we’ll reference part two a little further down the page).

This is not a post about how to use Instagram well: this is a post about how to make the case to use Instagram in the first place. When I run workshops there are very often organisations represented that simply won’t yet allow the (enthusiastic, knowledgeable, social-media savvy!) attendees to set up a Library Instagram account… Sometimes there are librarians who are allowed to create the account but a little bit nervous about not being expert photographers, and we’ll talk about that as well.

The subtitle of this post is ‘10 reasons to set up a profile’ and rather than being the reasons I’d personally choose, these are meant to be reasons to give to senior managers who are not convinced setting up a library account is the way to go.

So here’s the scenario: you ask to set up an Instagram account for the Library, and the decision-makers say no. Or they say: maybe, but show us why. Below are ten potential replies, some or all of which you can try working into the conversation.

1. Rival ORG X do it…

Without wishing to be too Machiavellian about it, pointing to the success of a comparable institution who already use Insta can be useful. Not necessarily to provoke a sense of competition or jealousy, but more to say ‘it can be done by an organisation like us, and here is the proof’. (I don’t actually think libraries are ever really rivals!) It’s reassuring to have an example of success to look to, and evidence that there are gains to be had that make it worth the time it takes.

In particular, it’s worth pointing people towards specific posts, not just the URL of the comparable account itself. So you can say ‘this is how X tackled the issue of covid-etiquette in the library, and here’s the response they got’ for example, or ‘here is how Y promote their Special Collections’ - build your case with specific examples that speak to the strategy / priorities of the managers. And talking of successful examples, this leads us on to the next argument…

2. We can learn from your main account!

This won’t be the case every time, but a lot of libraries have ‘parent’ organisations which will already have a profile on Instagram. So for example your local authority for public libraries, or your University for academic libraries. In itself this is a useful precedent to cite, but it’s also genuinely useful as a way to quickly understand what your community responds to.

Generic advice on what to post can be really useful, but nothing beats taking an approach based on the evidence of what your specific audience likes - the parent org’s Insta will show you. If you work at a University you can say, as part of your proposal for a library account, ‘we already know what our students respond to most - they like video content that gives them clear instructions on how to use services’ or whatever it is you deduce from the relative popularity of the Uni Instagram’s posts.

The actual mechanics of finding out what your audience already likes are these: go to the parent org’s Insta account on a PC (or Mac) rather than a phone / tablet, and hover over their most recent 15 or so posts in turn, noting the number of Likes and Comments for each (as show here). Some will be way higher than the average, and some will be way lower - you don’t need to be a social media analytics guru to spot trends and see what content types engage the audience most. Even for well established accounts this is an invaluable technique and I’d recommend it to everyone.

3. You didn’t let us do FB and Twitter either - but now you do

I’m sure there are exceptions but it seems like almost all libraries go through the same journey. In the 2000s they asked to set up Facebook accounts and were told no; eventually FB became so prevalent the powers that be changed their minds.

Leading up to and moving into the 2010s, everyone asked to set up Twitter accounts - no, they were told; stick with FB. Then eventually, Twitter became so prevalent the powers that be changed their minds.

And now in the 2020s it’s happening with Insta (and may well happen with TikTok also) - the same process, whilst risk-averse management get comfortable with the idea that Instagram is a) legit and b) here to stay (more on which later). So there may be some mileage in saying ‘history shows we WILL eventually get onto this platform so why not start earlier, gaining more experience along the way and reaping the benefits sooner?’

4. Instagram is the most engaged with social media platform

We covered this in detail in the previous post, part 2 of this series. The short version is the amount of people who DO something in response to Instagram posts (as opposed to people who passively consume a post but don’t press the Like button, or comment / reply, or reshare, or any other kind of interaction) is much greater that the amount of people who do something in response to Twitter and FB posts. Not only that, but libraries are part of the most engaged-with industries on Insta. So when you post, people react: that’s more important than, for example, sheer numbers of followers. It’s the first step to converting this into ‘off-site’ actions, like using resources, visiting buildings, or signing up for classes etc.

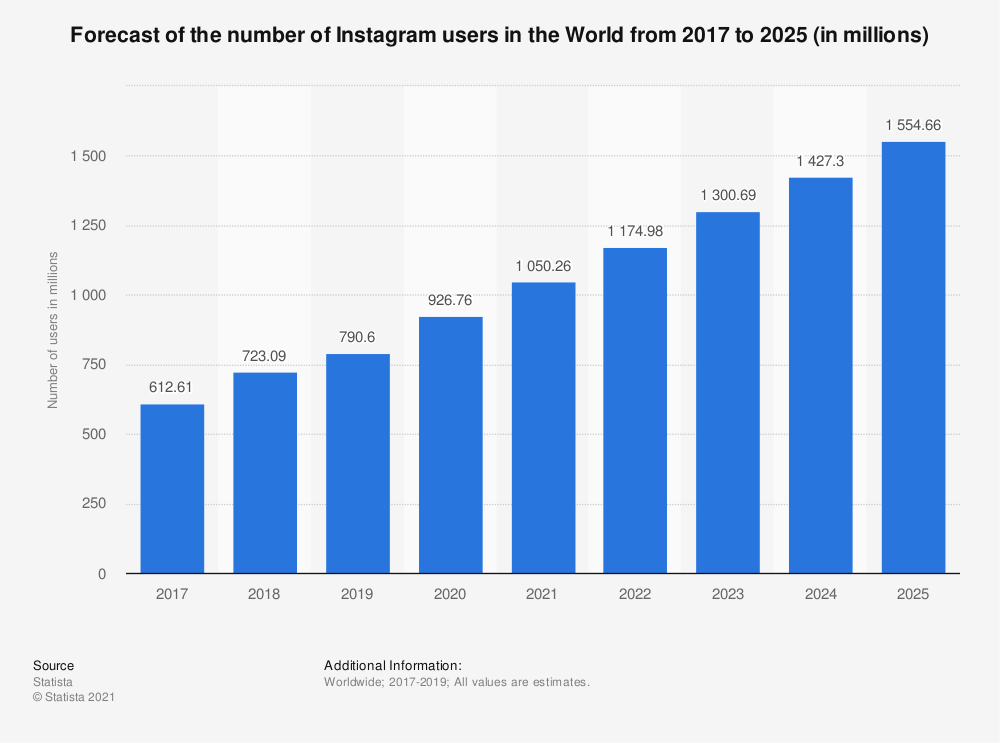

5. Instagram is here to stay

I personally wondered if Insta, with its meteoric rise, might burn brightly for a while and then fade. I was completely wrong. It is growing all the time in terms of sheer number of active users, and is predicted to continue to expand as this graph from Statista shows:

It’s also worth noting that the time spent on Insta each day by its users is also increasing according to TechJury, from 15 minutes per day at the start of 2019, to 30 minutes per day by midway through 2020.

All in all, then, Instagram seems extremely likely NOT to be one of those platforms where you invest a load of time and then see it all go to waste when the public moves on (like Snapchat was, for example).

6. Instagram is full of the younger demographic which is key to libraries

31% of Instagram users are aged 18-24, versus 17% for Twitter and 11% for FB - and in total over 70% on Instagram are 34 or under. There are a few library sectors not interesting in trying to get younger audiences to use their services, but not many: for academic libraries Insta is THE platform our students are all on, and for public libraries it’s populated by that key generation of potential library users who are younger than the overall average, but no longer children… Getting them to become life-long library users from the start of adulthood is a great goal, and Instagram can help with that.

7. You absolutely do not need to be a brilliant photographer or own a better camera than the one on your phone, to use Instagram successfully

For me Instagram has just the right amount of photo-manipulatability… Of course there are apps which allow you to do way more, but I don’t want EVERY option for editing; I just want some really useful ones. The combination of basic editing and flattering filters mean you can make the images you post on Insta look brilliant, even if you’re using a normal smartphone and don’t have a background in photography.

More importantly though, it is the subject of the image which matters most on Instagram, not the quality of the photograph. A brilliant picture of something prosaic will not get much engagement; a regular picture of something visually arresting will get Likes and Comments. (Obviously a brilliant photo of something really exciting is the best of both worlds, but the point is regular members of library staff can achieve success here without photography lessons and specialist equipment…)

8. You can now post from the desktop so staff don’t need a work account on their personal devices

Instagram was launched in October 2010. From then until the end of October 2021, you could not post on Instagram from a desktop: you had to use the app, unless you knew the hack.

That’s 11 long years for the idea to take hold that you need Instagram on your phone, and a lot of people don’t realise this is no longer the case (myself included until my colleague Megan told me about this the other day!). I’m delighted about this because I think some people, quite rightly, felt uncomfortable about having a work app on a personal device, so using Instagram instantly became something of a compromise, blurring those home-life / work-life boundaries. This is no longer the case: you can use it from instagram.com on your desktop, and keep those two worlds completely separate - potentially widening the pool of staff who feel happy to get involved with providing content for a library account.

9. IN THE CULTURAL SECTOR, INSTAGRAM USE IS HIGH

This means that there are LOADS of other libraries already there which we can learn from, and not only that but loads of museums, galleries, archives and other cultural sector organisations too. So many examples out there means it’s easier to find a model to suit the one your library would like to adopt, and means there are constant opportunities to learn, to develop new ideas, and potentially to develop partnerships too.

10. Last but definitely not least: we can improve the reputation of the library with Instagram

Instagram isn’t a hard marketing platform. (That’s part of what makes it fun to use.) What it does is keep the library in the mind of the user, showcase nice library locations, raise awareness of services and collections, and break down some barriers as to how people think about libraries in general. When used well, Insta will have a positive impact on the way your library is perceived, and help you deliver key messages. That’s argument enough for me on its own, but it’s not enough for everyone then there are nine other reasons to try above…

Good luck!